Session One - The World of the New Testament

Introduction

Why study the New Testament?

The beginning of Christianity.

The Context of the New Testament

Context is critical to a correct understanding of why, where, and to whom the New Testament was originally written, what it meant to real people who lived in real places (in terms of their language, culture, social structures, education and worldviews), and why we ended up accepting the 27 books that form the New Testament in our Bibles. We need to try to put ourselves in their first-century heads and see through their eyes as we read, interpret and apply the New Testament to their understanding, and our understanding, of Christian teaching and living. What was it like for them? What does it mean for us, living as we do at such a distance from the original events? The message has not changed, but the context has, over the ensuing 2,000-year period. We need to know how to read apply the New Testament today.

Before we plunge into the New Testament itself, let's set the scene by looking briefly at a number of important background factors:

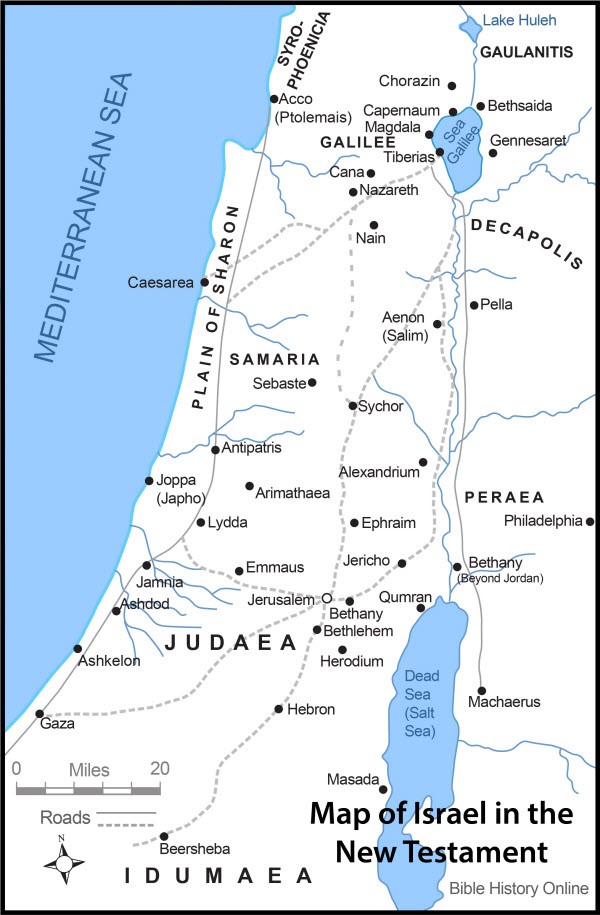

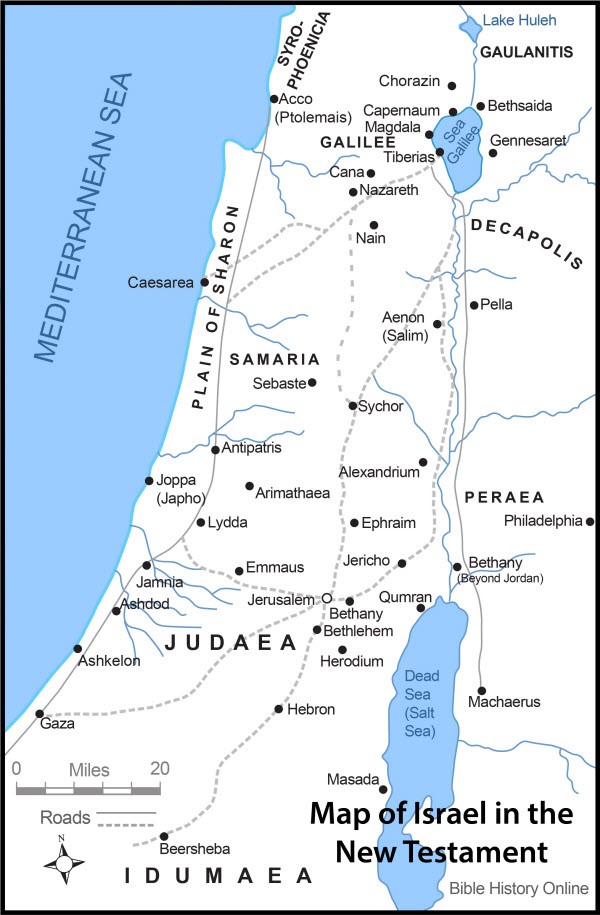

- the intertestamental period - the gap between the Old Testament and the New Testament era, in which Jesus lived where he did

- the world of Jesus, as a Jew, living in Palestine, a tiny (but strategically located and important) piece of land in a complex, contested Gentile world

- the role of religion in Jewish and non-Jewish history, thought, culture and praxis

- political players who had a role in Jesus' life and times

- the wider Graeco-Roman world that surrounded (and dominated) Palestine, politically and culturally

- the tensions, trends, and changes in the region under the influence of Hellenism and the Roman occupation

- the world of the Apostle Paul, who wrote a third of the New Testament and led much of the early church

We will explore how what started out as a local Jewish sect rejected by most educated Jewish leaders at the time became the dominant (and ultimately only legally permissible) faith that stretched across the entire Roman Empire in just a few generations.

Inter-Testamental Period

The prophet Malachi, whose ministry probably came to an end around 425 BC, wrote the last book of the Old Testament during the period of Persian occupation and rule over the nation of Israel. This was followed by 400 years of "silence", as far as divine revelation to Israel was concerned.

Persian domination continued until the rise of Philip of Macedon and his son Alexander in what is today Greece. Alexander ("the Great") conquered territory from Greece to India; Israel came under Alexander's power in 331 BC. When he died (childless) his territories were divided among his four generals. Two of those generals, Ptolemy and Seleucus, eventually came to hold the southern and northern halves of the kingdom.

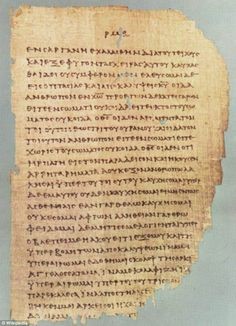

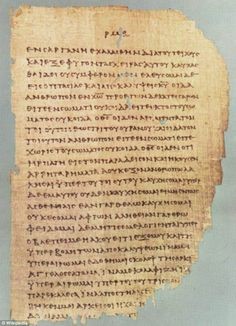

This resulted in a century and a half of Greek power and cultural influence throughout the Middle East. The Greek language became the second language of people who needed to do business or travel. In Israel, the typical first language of Jews was a Semitic tongue called Aramaic, very similar to Hebrew. But with the coming of Greek some Jews became at least minimally trilingual, knowing enough Hebrew to understand the Scriptures when they were read weekly in the synagogue, speaking Aramaic among themselves, and for those who needed to converse with outsiders learning at least some Greek on top of all that; some would have known Latin as well.

This continued after Rome conquered that portion of the ancient Mediterranean world; a common language throughout the eastern half of their empire suited; most Romans by birth would have spoken Latin. Rome was the linguistic fault-line between east and west.

During the time that the Jews were dispersed to Babylon (from 597-581BC), many had lost the ability to speak and read Hebrew and thus could not read the Scriptures. With the establishment of Greek as the universal language, a solution presented itself. From the 3rd century BC to 132 BC, Jewish scholars translated the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek. The resulting text, called the Septuagint (named for the seventy who translated the text, in the city of Alexandria), is what most of the New Testament writers quote. It also introduced the Greek word Christ for the Hebrew Messiah (lit. the "anointed one").

Greek language and culture spreading throughout the region also meant that Greek forms of religion spread. Judaism was an exclusive religion, so the era of Greek influence (up to the 160s B.C) led to turmoil. Some Jews accommodated Greek ways of life, including learning and religious customs; others rejected these changes.

In the second century BC, the Seleucid rulers (named after Seleucus) increasingly demanded that exclusive Jewish practices be abandoned. One of their kings, Antiochus Epiphanes (who reigned from 175-164 B.C.), decided to defile the temple in Jerusalem and to establish an idolatrous religion there. This led to guerrilla warfare. Jewish patriots took up arms, led by Judas Maccabeus (or "the hammer") and fought a war of independence from 167 to 164 BC; by 142 BC the entire land of Israel was liberated from Seleucid power.

This was followed by a century of independence for the Jewish nation, under the Hasmonean dynasty, after Judas's great grandfather. In 163 BC there was a conservative Jewish backlash against the Greek practices of the day such as not keeping Sabbath, not observing the dietary laws according to the book of Leviticus, not believing in Jehovah (Yahweh), the one God of Israel, and not recognizing Israel as a promised land and the temple as a holy place with God-ordained customs. (To this day, Jews celebrate the liberation of their land and period of independence with the festival of Hanukkah, or Feast of Lights, honouring the Maccabees for cleansing the temple.)

The distinction between Jews and others ("Greeks") can be seen throughout the New Testament.

The final era of historical and political background to New Testament was the period of Roman rule. Slowing advancing eastward Rome conquered more and more territories. The Roman General Pompey entered Jerusalem in 63 B.C. In 37 B.C. Herod the Great was made king of the Jews by the Roman Senate.

Jesus was born during the reign of Herod the Great, lived in Galilee under Herod Antipas, and died in Jerusalem during the procuratorship of Pilate and the high priest-hood of Caiaphas. Roman rulership of Judea was from Caesarea Maritima (not Jerusalem).

The Inter-Testamental period ended with the arrival of John the Baptist, the forerunner to Jesus Christ, and the inauguration of a New Testament, or covenant, between God and man.

The World of Jesus

Jesus was a Jew. He grew up in a Jewish household. The first disciples were Jewish. The world view of his family and friends was Jewish. Jewish practices centred on:

- the Law - dating from Moses - and traditions based on the Old Testament & history

- a priesthood, based on the Law and dating back (in various forms) to the Aaronic priesthood of the wilderness wanderings.

- offerings, festivals, institutions, dietary laws, taboos and traditions.

- the land of Israel - the land was considered to be God's gift to his people. The promise reached back into the days of the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who dwelt in and around the land but did not possess it (cf Gen 12:1-3).

- the second temple- the epicentre and central symbol of Jewish life and nationalism; shortly after the middle of the sixth century BC Babylonian overlordship was replaced by Persian rule. Jews were allowed to return to their homeland and to begin the restoration of the Jerusalem temple, which had been destroyed by the Babylonians.

- synagogues (at a local level), scattered throughout much of the Roman Empire, were places that were devoted to the study, training, preaching and teaching of the Law. The Synagogue was the place where most Jews went to be educated by the rabbis, attend social functions, and hear messages from a rabbi or qualified layman on the Sabbath. There was only one Jerusalem temple, but there were many synagogues. Although the origin of the synagogue is hidden in obscurity, by the first century it had become a central Jewish institution, a kind of community centre. Unlike the temple that was presided over by the priests, the synagogue was a lay organization that allowed broader participation, such as Jesus' reading from the Torah in the synagogue in his home town Nazareth (see Luke 4:16) and Paul's extensive use of synagogues in his missionary work (see Acts 18:4).

- Messianic expectations - Most people who were looking for the Messiah were expecting a strong leader who would expel the Romans from Judea.

Model of the Second Temple

Jewish beliefs and religious actors

Jewish national and religious life at the time of Jesus was quite diverse. There were different schools of thought and convictions about how God wanted them to live and how He would bring about His ultimate purposes. There were large Gentile communities in Palestine. There were main four leadership groups: Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes and Zealots. Pharisees and Sadducees emerged during the Hasmonean Dynasty. There are also other groups we will consider briefly.

The Pharisees were the largest sect at the time of Jesus. They were experts in the Law, both the written laws of Moses in the Old Testament and the oral interpretations and additions that had begun centuries earlier and would continue for centuries until they were written down, well after the time of Christ. The Pharisees offered the people a detailed knowledge of right and wrong, and sought to apply the Torah in daily life, but they were very legalistic, with 613 commandments and over 1000 additional amendments. Their passion was keeping the Law and pleasing God in every possible context. Many of the Pharisees tended toward self-righteousness, separateness and pious judgementalism, thus creating exclusiveness and barriers between themselves and ordinary people (cf John 7:49). The Pharisees believed in angels and spiritual beings, the resurrection and eternal rewards and punishment. Pharisaic worship practices led to some of the models adopted in early Christian church services, with patterns of prayer, hymns, and preaching.

The Sadducees (the most powerful and politically connected group) denied most of what the Pharisees affirmed. They did not explicitly deny God, but questioned belief in an afterlife or resurrection of the dead, thus making it possible to compromise with Greek culture, as the Romans grew intolerant to pay tribute to them, and once Rome had invaded Israel, to make their peace with the new occupying forces. They believed in free will. They rejected the oral laws that the Pharisees had added to the written scriptures and rejected doctrines that could not be taught from the five books of Moses. Most of the high offices in the religious courts, most notably the Sanhedrin (the Jewish supreme court), were tightly controlled by the Sadducees. The priesthood of the great temple of Jerusalem was also controlled by the Sadducees.

Religion, to the majority of the Sadducees, was a convenient way to gain power, money, and influence. They were treacherous, even to each other. Jewish historian Josephus had this to say about them: "The behaviour of the Sadducees one towards another is in some degrees wild; and their conversation with those that are of their own party is as barbarous as if they were strangers unto them." Because of their links to the aristocracy and civil authorities, they did not survive after the destruction of the temple in 70AD. The Pharisees believed that if one was deported from the land and could not offer literal animal sacrifices for the forgiveness of sins in the temple in Jerusalem it was acceptable to replace prayer, repentance, and good works for those sacrifices. The Sadducees did not agree; without a temple, they could not have forgiveness of sins and so died out.

A third group were the Essenes. They were separatists, the ascetics, of the day. The most famous group that we know lived at a site on the shores of the Dead Sea called Qumran, where the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered just after World War II. They looked for two Messiahs, one who would be a king, another a priest. They removed themselves from what they believed to be the corrupt world, even of the rest of Judaism around them and occupied themselves with a disciplined communal lifestyle. They thought the solution to Israel's ills and occupation by Rome was to obey the law and await God's spectacular intervention into history to throw off the yoke of the oppressor.

The Zealots were activists, revolutionaries, or freedom fighters, opposed to Rome's rule. They hoped to repeat the Maccabean miracle but were brutally slaughtered in a revolt they sparked from 67-70 AD. They believed that God helps those who help themselves and if they would take up arms and rebel against Rome He would intervene and bring them independence.

Other groups

Scribes

"Scribes" were the professional copiers of the Law, who also assisted rabbis in the interpretation of the Law. They were like the jurists and lawyers of the day. They were close to the Pharisees.

Herodians

The Herodians held political power, and most scholars believe that they were a political party that supported King Herod Antipas. The Herodians favoured submitting to the Herods, and therefore to Rome, for political expediency. This support of Herod compromised Jewish independence in the minds of the Pharisees, making it difficult for the Herodians and Pharisees to unite and agree on anything. But one thing did unite them Ś opposing Jesus. Herod himself wanted Jesus dead (Luke 13:31), and the Pharisees had already hatched plots against Him (John 11:53), so they joined efforts to achieve their common goal.

Samaritans

The Samaritans were descendants of Israelites who intermarried with aliens imported into the region after the fall of Samaria in 722BC. They set up their own temple and sacrifices, although they worshipped God as did the Jews. Their Scriptures were limited to the Pentateuch. Samaritan communities still exist in Israel.

"Pilate", Caesarea

Jesus as a Jew

Jesus was Jewish before anything else. He was not Western, white, blond, blue eyed and straight out of Hollywood central casting. See his genealogy. Jesus was raised a Jew. He was circumcised on the eighth day (Luke 2.21), had a common Jewish name, Yeshua, 'he [God] saves' (Matthew 1.21), the fifth most common Jewish name; 4 out of the 28 Jewish High-Priests in His time were called Yeshua. After his birth, Jesus was presented in the Jerusalem temple (Luke 2.22; cf. Deuteronomy 18.4; Exodus 13.2 12, 15). A sacrifice was offered for him, which indicated that his family was not wealthy (Leviticus 12.2 ,6, 8; Luke 2.22-24). Jesus was raised according to the Law (Luke 2.39). By the age of 12 he was found in the temple precincts "both listening and asking questions" (Luke 2.46). Every year His family went up to Jerusalem to celebrate Passover (Pesach) (Luke 2.41-43) a tradition Jesus continued (John 12.12; Mark 14.12-26). Jesus kept the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukk˘th, 'booths') (John 7.1-39). John 10.22-23 may indicate that Jesus celebrated the Hanukkah festival which commemorated the 2nd century B.C. rededication of the Temple under the Maccabees. He attended synagogue every Sabbath and read Hebrew (Luke 4:16-21; Mark 1:39; Matthew 4:23; 9.35). His first followers were Jewish.

Widening the Circle - The Graeco-Roman World

Christianity was initially seen as a sect of Judaism; their deity (every people group had its own particular gods) was the "Jewish god". The world view around the Mediterranean was predominantly based on Greek culture, polytheism and philosophy (lit. love of wisdom). The earliest Christians outside of the Jewish community were first-generation believers, the first who left their pagan roots (see 1 Corinthians 6:10, 11) and (often) social structures.

While Judaisers in the church sought to impose Jewish laws on converts to Christianity, Gentile believers did not generally understand or take an interest in the inner workings of Jewish monotheistic/ nationalistic theology (although there were Jewish converts in many societies, including in Rome). They had no New Testament, no clergy and no church buildings. The Lord's Supper (based on a Jewish festival, Passover) was a regular feature of worship.

Other Religions

Greek/Roman society was characterized by religious diversity.

- Greek religions were represented in "classic" myths about gods and goddesses who lived on Mt Olympus, with Zeus as the head of a pantheon of gods; he was later called Jupiter by the Romans, who adopted much Greek religious thought and re-named the old gods to suit themselves. The myths were wrapped up in elements of nature, different parts of the universe deified with elaborate stories explaining how they came to be: Apollo the sun god who drove his fiery chariot across the sky from east to west every day, Dionysus or Bacchus the god of wine, and many more. Such myths appealed because they seemed to explain the unknown and the seemingly random or erratic parts of the universe; they provided explanations for why tragedies occurred. Apart from Jews and Christians, people in the ancient Mediterranean world were almost all polytheists. Cities and towns were littered with gods (the most famous being Zeus; other popular gods included Hera, Apollo, Artemis, Poseidon, Aphrodite, Athena, Demeter, Hermes Ares and Hades; there were many others: Asclepius, the god of medicine, Persephone, Demeter's daughter, Gaia the earth goddess, Hecate, and so forth; in addition, every village had its own gods.) Gentile Christians lived in a polytheistic world that regarded (and persecuted) them as atheists.

Jesus' challenge to the disciples to tell him who they thought he was (Matthew 16:13) took place at Caesarea Philippi, at the headwaters of the Jordan River, where there were temples to numerous gods, including Pan, the Greek god of Nature.

- Emperor worship - the belief that the emperor becomes a god initially upon his death. As the first century unfolded people came to believe that Caesar was a god during his lifetime; some emperors encouraged this viewpoint this led to tensions, particularly with Christians.

- Sects known as the "mystery religions", or cults, often worshiping foreign gods, eg being baptized in the blood of a sacrificed bull, or having a special meal "eating with the gods", or even to have sexual relationships in a temple with a priest or priestess who was in fact little more than a prostitute, believing that during the sexual act one was achieving union with the god or goddess of that temple. Most mystery religions taught equality among their followers. Slaves, senators, men, women, native-born Romans, and barbarians could see each other as equals when the cults came together, often at night under the cloak of darkness.

- Greek philosophies:

- Epicureans whose slogan "eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow you may die" is still known in today's world. They believed that the material is the only reality. There is no need to be anxious about death; we need to focus on pleasure in this life, free from pain, anxiety or frustration, and make the most of what we have (without being over-indulgent).

- Stoics were the exact opposite of the Epicureans in most of their beliefs of accepting ones predetermined fate courageously. They believed that the world is guided by a "logos", or divine reason, that guides everyone, so we can afford to be tranquil in the face of adversity.

- Cynics and Skeptics were the most pessimistic and countercultural of the various philosophers. They did not follow the gods.

- Sophists were teachers who went from city to city, reaching for fees; they practiced rhetoric and could argue for any point, true of false.

These (and similar) lifestyles appealed to those in the upper classes who had time to study with philosophers.

Read about Stoics and Epicureans in Acts 17 as Paul dialogues with the philosophers in Athens. Stoics believed that God was so close to the world that He was a part of it. Epicureans believed that He was so distant as to be unknowable. Paul affirms elements of both perspectives while rejecting elements of both of them. The wandering nature of the cynic beggar living on handouts from others show some points of similarity with Jesus' disciples when they went out two by two and relied on others' hospitality, but there are noticeable differences. The disciples proclaimed an optimistic message whereas the cynics proved far more pessimistic.

- Gnostic beliefs went back to Greek philosophers who held that the material and immaterial worlds were separate and different, that matter was by nature evil and only spirit good. Followers believed in redeeming the spirit or soul, but not to look for a bodily resurrection as Jews and Christians did. Such beliefs could lead to two quite kinds of lifestyle. Some, believing there was no hope for the body tried to deny the body normal appetites, fasting, abstaining from alcohol, leading a celibate lifestyle. Others believed that nothing could be done to keep the material part of a person from evil, and encouraged indulging it as long as one was trapped in this material body.

Gnostics believed that there was a divine spark inside many people waiting to be fanned into flame through secret knowledge; as we read the Epistles we see that Christianity had to confront these claims. Gnostics who believed that the supreme God would not touch the (evil) material world, and that the creator of the world was in fact a lesser god, could not conceive of God coming in human flesh; they rejected the notion of the Incarnation.

What did the pagans think of Christianity?

Steeped in ancient, esoteric, often local religions of their own, pagans had mixed feelings about the Jesus and the Gospel:

- a mortal would obviously want to become a god, but why should a god want to become mortal? the world was made for the benefit of the gods, not people

- why would a god be interested in "sinners" and the "refuse" of society? Gods had no need of humans

- why would a god choose a poor woman or no royal or priestly ancestry to be his mother? gods were hierarchical and had no interest in lower orders

- why would a good allow humans to mock and crucify him?

- how could a dead human (a confirmed criminal) become an immortal god?

- why should anyone accept absurd tales of resurrection?

- Christians worshipped two gods (Jesus and his father), why object to polytheism?

- why worship a corpse while attacking those who made statues of their deities?

- why follow a religion from rebellious, backward Palestine, which was full of losers?

- worship of the gods promised a good time (gladiators, circuses, chariot races, food, drink, free sex), whereas Christians avoided these

The World of Paul

It is also important to understand the worldview of Paul, given his role in spreading the Gospel, leading the early church and positioning the Message for a non-Jewish world. He was a man of two cultures.

Judaism, in Paul's day was very influential, with followers throughout the Roman empire. It was considered to be the "official" religion of the Jews, and as such, was deemed legal by Rome. Although first and foremost considered to be a religion for ethnic Jews, there were many non-Jews (Gentiles) who converted to Judaism's monotheistic and ethical beliefs, which had wide appeal to those who had already embraced much of its tenets found in philosophy, but were dissatisfied with the limitations found in Greek philosophy. They underwent rituals to become Jewish. Some were sympathetic to second temple Judaism, but did not undergo ritual conversion; among these was Cornelius, the first Gentile convert (see Acts 10). The Bible refers to them as "God-fearers".

In Paul's day, the "rabbis" were the teachers and exegetes of the sacred writings found in the Torah. Paul studied at the feet of a Rabbi named Gamaliel (Acts 5:34; 22:3).

Paul (his Greek name, translated from the Hebrew name Saul) grew up in a Greek environment. He was raised in a Hellenistic (Greek thought, education, influence and customs) society in Tarsus, a city in Cicilia; a university town, port, and commercial centre. Most Jews in the world probably spoke Greek and were influenced by a world very different from Old Testament times. In Acts 21, we find that Paul spoke fluent Greek to the Roman military captain, Lysias, to stop a crowd from lynching him. William Barclay has observed that, "The captain was amazed to hear the accents of cultured Greek coming from this man (Paul) whom the crowd were out to lynch." Paul was fluent in Koine Greek, a Greek tongue commonly spoken in his native city of Tarsus, as well as being fluent in Classical Greek, which indicates that he had been exposed to Greek learning at the university level. And yet, he called himself a Hebrew of the Hebrews" (Philippians 3:5). We do not know whether Paul met Jesus during His earthly ministry.

Through his father, Paul inherited Roman citizenship, a privilege rarely conferred on Jews. As a result of his family being wealthy tentmakers and Roman citizens, he was no doubt exposed to ranking Roman officials, and Roman practices, law, and customs.

The launch of the church occurred at a critical time:

- much of the known world was subject to a single empire, which meant that communications were more viable than during any previous period in history

- a more or less united cultural and legal framework, the so-called "pax Romana" ("Roman peace") extended across much of the known world from Italy to India (Paul lived under five Caesars)

- Greek and Latin (the language of Rome and of legal proclamations), unified millions traditionally divided by common, written languages (making mission easier to accomplish)

- transportation systems (roads, ships) were state-of-the-art by ancient standards

- Gentile "God fearers" (who lived by Jewish standards but were not circumcised) influenced non-Jewish communities

- international trade flourished and travel was easier than ever before (note the range of cultures described in connection with the Day of Pentecost in Acts 2)

- many cities had Jewish communities; this would prove helpful as the first missionaries went straight to synagogues to base themselves and preach the message

Some first century churches were strictly Jewish, in both composition and praxis, eg the early church leaders in Jerusalem, led by James. They did not think of themselves as members of a new religion separate from Judaism.

Others progressively moved away from the Jewish roots of the Christian faith and became exclusively Gentile.

While models for church life in our contemporary world often cite the first chapters of Acts, this can be misleading. Christian communities in the (predominantly Gentile) Empire did not necessarily reflect what church life in Jerusalem looked like structurally or in terms of worship practices. It is important to read and interpret the New Testament contextually.

Hellenism

Hellenism is the term used to describe the influence of ancient Greek culture, science, ideas and civilization on the peoples the Greek and Roman Empires conquered or interacted with, from around the time of Alexander the Great (323BC).

New Testament theology was impacted by Hellenic ideas. For example:

Logos. John 1:1 is one of the many examples in which Christian Scriptures use Greek concepts to explain a truth: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God." This "Word," referring to Jesus, is the Greek logos. Logos originally meant "an opinion, word, speech, or reason," but the Stoics came to affiliate it with the spiritual creative force in the universe-reason within the physical. This is related to Plato's "form," which he defined as the ultimate, perfect model held in the mind or realm of the Creator on which earthly things are based. Jesus' identification as the logos means that His teachings directly reflect the universal truths of creation.

Christianity eventually broke away from Judaism (Jerusalem was destroyed in 70-AD) and spread rapidly among the Gentiles throughout the Mediterranean world. However, although Greek culture exerted influence on the spread, language, and culture of Christianity, and even spawned unbiblical cults, it did not affect the orthodox theology. The story of a single, triune God, and the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ remain untouched by Hellenism. Early Christians went to their graves in order to ensure the gospel message stayed true. Hellenism in the days of the early church remains an example of how to use a culture to spread the message while not allowing the culture to change the message.

Why is this important?

Why do we care?

- Because this was the moment when God came into human history as a man (see Galatians 4:4-7).

- The beginning of Christianity - Church history, theology - Luke 1:1-4

- Everything changed from this point.

- As we have seen, the circumstances (common language, good communication, safe travel, good roads, etc) created a perfect time for world evangelism.

- We (and Western civilization) are heirs of the Jewish and Graeco-Roman influence in Christianity.

- Our typologies, church traditions and architecture, Christian culture, the words of many of our songs, terms used regularly in church, come from this period.

Jesus Christ changed the course and meaning of human history. He revolutionized an empire and occupies the centre stage in the human story. There has never been anyone like Him. The greatest revolutionaries pale beside him. Consider the facts.

Jesus was born in an obscure village, in a remote part of the Roman Empire, the child of a peasant woman. He grew up in another (working class) village. Many looked down on him as illegitimate. He worked in a carpenter shop until He was thirty. No one knows how long his mother's husband Joseph remained in his life.

For 3 years, He was an itinerant preacher, whose message was popular at a local level but rejected by the religious authorities. He never owned a home. He never wrote a book (although more books, poems and music have been written about him than about any other human being). He never launched a political party and never held an office. He never had a family. Apart from Jerusalem He never put His foot inside a big city. He never travelled two hundred miles from the place where He was born.

While He was still a young man, the tide of popular opinion turned against him. His friends ran away. One of them denied Him and another sold him out to his enemies for the price of a common slave. It took nervous Roman authorities only one swift stroke to scatter his band of followers and put him to a horrible death. He went through the mockery of a trial. He was executed by being nailed to a cross between two thieves, a form of capital punishment reserved for the worst criminals.

While He was dying, and his shocked mother looked on, His executioners gambled for the only piece of property He had on earth - His coat. When He was dead, He was placed in a borrowed grave through the pity of a friend. However, His friends claimed that they saw him alive again after three days; the authorities acted quickly to squash that story.

Nineteen long centuries have come and gone, and today Jesus is the central figure in the human race. His teachings overthrew an empire. Our calendars mark the time that has passed since his birth. All the armies that ever marched, all the navies that were ever built; all the parliaments that ever sat and all the kings that ever reigned, put together, have not affected the life of man upon this earth as powerfully as has that one solitary life. His movement has outlived every empire and culture with which it ran parallel.

Adapted from One Solitary Life, http://www.anointedlinks.com/one_solitary_life.html

The life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ changed everything. This is a good foundational reason for us to understand the New Testament.